Dear Members,

I am delighted to be able to announce the winners of the 3rd John Bird Dreaming Award for Haiku. The response to the competition was fantastic once again, with 260 poets submitting their haiku from all corners of the globe. I would like to extend a huge thanks to all poets for contributing their poems and look forward to receiving their entries in the years to come.

Our judges have chosen their top three haiku and honourable mentions whose poems appear below. I would like to thank the judges, Hazel Hall and Lyn Reeves for their diligence and support for this award. I would also like to express my deep gratitude again to Ron Moss for providing the winners with beautiful ink drawings featuring their poems.

Rob Scott,

Vice-President, AHS

3rd John Bird Dreaming Award for Haiku — Results

Hazel Hall and Lyn Reeves, Judges

Joint Judge’s Report

Our thanks to all the poets who submitted haiku to the John Bird Dreaming Award. It was a great pleasure to be working together to honour a great Australian haiku poet. We looked for haiku that would measure up to John’s own work. Every poem written is significant to its creator and we have learned a great deal from each poet. Nevertheless, there are always images that remain only in the poet’s heart. Haiku teases out the wabi-sabi: the beauty and awe in imperfection. It can show us the importance of tiny things. We share our vulnerabilities in our poetry. This makes judging exciting, difficult and incredibly humbling.

We sought haiku that was subtle, with room for contemplation. We wanted to find the wonder; the ‘aha’ moment. Bearing in mind that many short Japanese songs in the Man’yōshu were sung, we also looked for haiku that flowed like unrhymed songs.

No poem should contain unnecessary words. Although haiku were once based on the 5/7/5 syllable count, today’s haiku tends to be shorter and more flexible. However, there were also some fine longer haiku reminiscent of the waka style, that found their way into our short lists; poems that did not pad their lines to achieve the 5/7/5 structure.

Originality was high on our list of desirable attributes. Haiku must offer an original thought, or a new way of approaching familiar themes. Traditional haiku contained a kigo, or reference to a particular season. This has since relaxed and become a reference to natural phenomena associated with that season. Although it is possible to write haiku without a kigo, we still enjoy a reference to the natural world, or a sensory image that one can relate to.

Most of the 260 entries came in multiples of three, and it was a difficult task to whittle this down to a total of six awarded poems. To all the fine poets who were not included in this final group, we urge you to send out your best work for publication. To those just beginning to write haiku, please read widely and consider the wealth of essays available online.

We are grateful to the Australian Haiku Society for entrusting this year’s selections to us. Congratulations to the winners!

Hazel Hall

Lyn Reeves

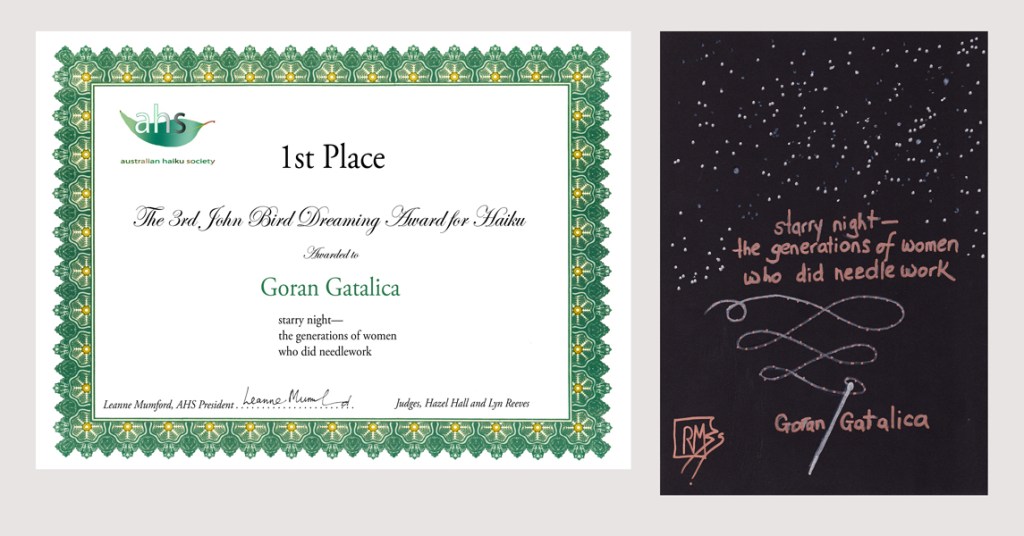

First Place

starry night—

the generations of women

who did needlework

Goran Gatalica, Croatia

Francis William Bourdillon (1852-1921) once wrote ‘The night has a thousand eyes / And the day but one’. This sparkling haiku begins with an image of starry eyes looking down on the world — or perhaps a pin-pricked galaxy where the light of heaven shines like starlight. In nine words the poet celebrates women and an art form that was once a necessity. Alliteration links each line: night / generations /women/ needlework. The assonance in ‘women’ and ‘did’ emphasises needlework as an active pursuit. Many working-class women sewed to earn a living. Privileged women stitched as a necessary accomplishment and to relieve themselves from boredom and isolation. Needlework was once part of the Australian school curriculum for girls. Sewing circles were, and still are, a means of communication where women share the latest gossip. Myriads of stories have been passed from one generation to another. In this throw-away society, stitching still continues.

Hazel

This haiku immediately grabbed my attention and would not let go. It is imbued with yugen: “a profound, mysterious sense of the beauty of the universe … and the sad beauty of human suffering.“

There is reverence here, not only for the magnificence of the sky stitched with stars but also for the women who, throughout time, have patiently created and mended the necessities for life, objects both practical and aesthetic. A simple occupation, but an essential one, by which skills, stories and traditions were passed from one woman to another. Also present is a sense of nostalgia for crafts such as needlework that are being replaced by machine-made, throw-away consumables. A winning haiku, celebrating the enduring value of women’s work that connects lives across time and the universe we briefly inhabit.

Lyn

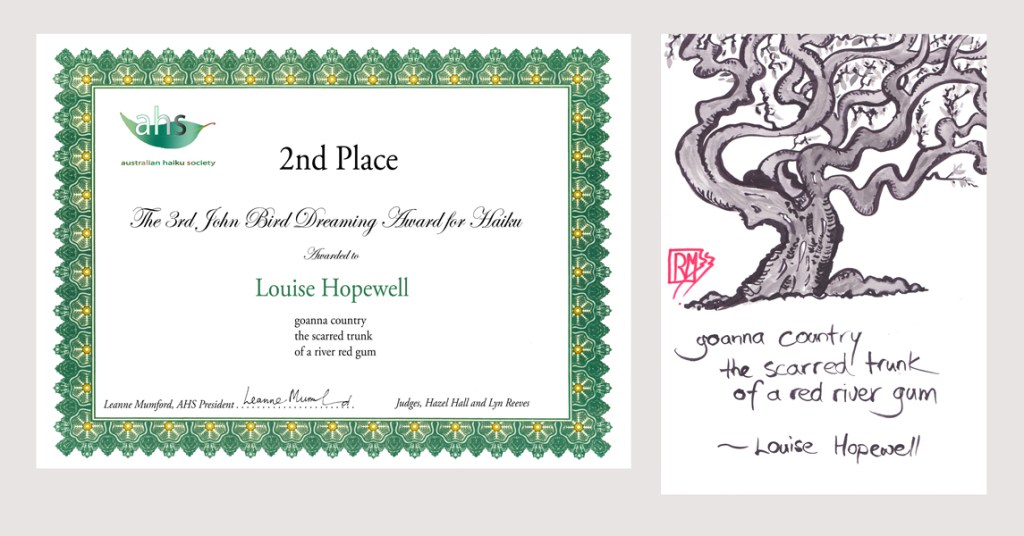

Second Place

goanna country

the scarred trunk

of a river red gum

Louise Hopewell, Australia

This haiku is filled with stories. The goanna is totem for the Bundjalung people, who, it is told, arrived at Goanna Headland. It is also totem for other first nation peoples, including the Wiradjuri, who belong to three rivers: the Murrumbidgee, Lachlan (Gulari) and Macquarie (Wambool). Each line holds more dreaming room. The scarred trunk, where bark has been removed for various purposes, is also a harsh reminder of scars left on the country by white settlers and in the hearts of its original people.

Words flow into each other like a river. The short ‘u’ sound (country, trunk, gum) assonates the end words. Stolen land, culture and children, massacres and the practice of forced integration with white people has had a devastating emotional effect. A poignant haiku, reminding us that it’s time for truth telling and changes to Australia’s history books. Time for all of us to listen.

Hazel

Goanna country could be the traditional lands of the Wiradjuri or Bundjalung peoples, who both revered the goanna as a Creator spirit. An important food source with totemic significance, the goanna symbolises the spiritual connection of First Nations People to land and history. The Red River Gum was favoured for making canoes, shields, coolamons and for cultural reasons. Scarring was caused by removing a slab of bark, leaving an area of sapwood exposed. Those Scar Trees that remain in the landscape, survivors of destruction by vandalism, agriculture, climatic events, colonial occupation, are present reminders that the country is and always will be Aboriginal land.

The effect of this haiku lies not only in the story it tells but also in the simplicity and strength of the language. Hard and liquid vowels work together to create both solidity and flow. No adornment, no unnecessary words, just the potent imagery of goanna and a scarred red river gum.

Lyn

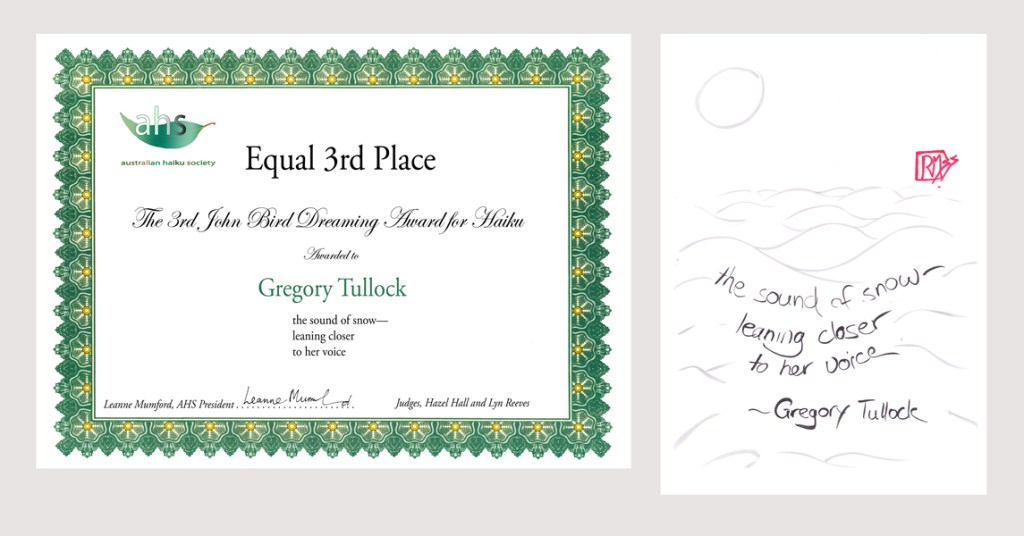

Equal Third Place

the sound of snow –

leaning closer

to her voice

Gregory Tullock, USA

This haiku is a moving study of love and/or grief. What is the setting? A seasonal kigo in line 1 shows us that it’s winter and snowing. The chilly atmosphere suggests that something momentous is or was happening. Is the poet with a lover? In a hospice, listening to the last words of a loved one as snow falls outside? Or by a graveside covered with snow? But what is the ‘sound of snow’? Its flakes can be noiseless to the human ear. Despite this, there is a deathly stillness suggested by this image. The poet’s continued use of sibilants (the soft ‘s’ in ‘sound’, ‘snow’, ‘closer’ and ‘voice’) suggests that both the snow and voice are barely heard. Or are they only in the poet’s imagination? By playing with the cusp of sound, we are shown what might be the poet’s heartbreak and longing in this subtle, dreamlike poem.

Hazel

A sensual poem with strong auditory imagery that creates an atmosphere of mystery and depth. The use of sibilance echoes the hushed, muffled sound of snow, suggesting gentleness and an intimacy which is heightened by the second line “leaning closer”. The final line, “to hear her voice” strengthens this feeling. This poem is strongly effective in the way it draws the reader into the mood and mystery of the moment. It suggests but does not explain, inviting the reader to complete the poem for themselves.

Lyn

Equal Third Place

dry grass . . .

the fencepost cat tracks

something doing something

Sandra Simpson, New Zealand

The poet has configured this fascinating haiku to show us a cat’s essence in a visual picture of stillness, movement, silence and sound. The first line, ‘dry grass’ is followed by an ellipsis, hinting at barely heard rustling of the grass – space to wonder what is coming. The cat is elevated: on the fencepost looking down like a king. One imagines the animal, sitting deathly still moving only its eyes: a further use for the ellipsis of line one. In the final three words, the poet contrasts this stillness with ‘something doing something’, opening our minds to a wealth of small creatures: mouse, skink, mantis, and more. Soon the cat will pounce and ‘something’ will stop doing whatever it’s doing. We become voyeurs as the cat plays with its victim. Suggested, never ‘told’, this poem references both animal and human kingdoms. Some humans take the lives of both too readily and easily.

Hazel

This is not just a cat on a fence. It is the fencepost cat – a description that immediately imbues it with feline authority. This is the cat’s domain and it suspects an intruder. We are not told what the cat tracks (nice chime here). I like the humour and karumi (lightness) of this haiku, replete with the essence of cat, the sensuality of its movements nosing about in the dry grass, curious, in charge and inscrutable.

Lyn

Honorable Mentions

air strikes

a toddler points

to the sky

Alvin B. Cruz, Philippines

This short, topical haiku echoes the brevity and waste of life in times of war. As rockets rain down, a small child points to the sky: the reaction of a toddler who cannot yet comprehend danger. The poet does not offer an outcome, but one visualises a mother gathering up her child in panic, as she attempts to rush for shelter. The poem is structured so that its end words draw us to the sky, ground, then sky again. Sounds of war are emphasised in the long ‘i’ sound (strikes, sky), bringing to mind the whine of rockets. The poet then contrasts this by using sibilants (strikes, points, sky) to suggest the innocence of a tiny child. Those watching the media on their screens can become desensitised by the terror of armed conflict. A haiku reminding readers of what is happening to children and its likely impact on future generations.

Hazel

Basho’s description of haiku as what is happening at this moment in this place might at first seem not to apply to this poem, but it presents a reality taking place continuously at this time in conflicts around the globe. We observe this reality constantly on television and in our newsfeeds. It becomes part of our everyday experience so that many of us may wish to turn away, to tune out from such devastation inflicted on the innocent. The poet zooms in on a toddler – the age when a child is discovering their world through pointing at things to learn about them. This close-up encounter with a single toddler highlights the circumstances of thousands in a way that is relatable and personal, giving the haiku emotional depth and resonance.

Lyn

a green tree frog

in the Bromeliad’s well

bird song

Leonie Bingham, Australia

Bromeliads are pollinated by insects and other small creatures. A green tree frog, native to Northern Australia, hops into a Bromeliad’s rosette and a bird sings. Green is the colour of life. Although the poet leaves the bird’s identity to our imagination, the singer is likely to be a carnivore. Magpies, currawongs, butcher birds and grey shrike thrushes are all singers. One can imagine the bird listening for movement inside the rosette. On musing more deeply, the reader might explore how seemingly attractive situations can sometimes lure one into difficult, even life threatening, situations. Does the frog find an insect and croak after its meal? Does the bird then sing after devouring the frog? The haiku sings too. Key words are brought together by using assonance (frog, Bromeliad, song). A cleverly written piece that builds tension throughout and reminds us that many humans also depend on a living food chain.

Hazel

Nature in its abundance and vulnerability suffuses this haiku. There is a symbiotic relationship between bromeliads and frogs, the plant supplying insects and larvae in its well in dry times and the frog supplying nutrients to the plant. Although rain is not mentioned there is a strong suggestion of recent showers in the word ‘well,’ the central cup of the flower that gathers and holds water. Birdsong amplifies this likelihood as birds are known to sing after rain. A sensory haiku of colour, sound, texture and shape, that draws attention to an ecosystem of plant, frogs, insects and birds and how their survival is interconnected.

Lyn

Discover more from Australian Haiku Society

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “Results of the 3rd John Bird Dreaming Award for Haiku”

Comments are closed.